ISABELLE BONZOM

TEN BREATHS

"a place for experiment and a return to the origins"

About Eric Fischl's "Ten Breaths"

French artist Isabelle Bonzom, a painter as well as an art historian, is the author of an in-depth conversation with American artist, sculptor and painter, Eric Fischl.

Two parts of their conversation were published by the French website CultureCie in Spring 2009. To read this published conversation, click here.

For this website covering the arts and culture, Isabelle Bonzom has also authored an essay on Eric Fischl's installation of sculptures exhibited in Spring 2009, at the Templon Gallery, in Paris:

“Ten Breaths, a place for experiment and a return to the origins"

When the visitor steps into the Templon Gallery in order to discover the “Ten Breaths” exhibition by Eric Fischl, he or she enters the shadow.

Transforming the space

The artist has plunged the space of the gallery into darkness but it is not the total obscurity of a dictatorial and oppressive black. On the contrary, a calming sensation emerges from this space that has become a mysterious cavity. Eric Fischl has totally transformed the space of the gallery into an installation full of nuances.

“Ten Breaths” projects a wide range of warm tints of earth colors, from warm blacks to the most luminous whites. The space is tinged with a variation of similar tones: colored, almost pearl-like grays, greenish umber, deep browns, burnt Sienna, crimson ocher, carnal red, gilded and rusted yellow ocher.

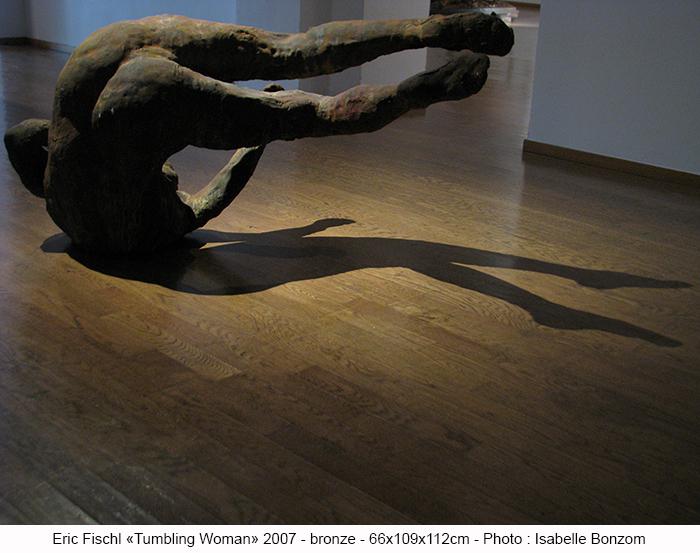

And yet, there are only the wooden floor, the girders and the white walls, the glass and the steel of the obstructed glass roof. The sculptures are displayed directly on the floor. They are made of bronze or resin covered with a patina nuanced with red and yellow ocher. Surprisingly, the show is very restrained. No excess, no flashiness. It’s rough and direct.

Fischl has succeeded in composing the emptiness and the fullness of his sculptures with the space of the gallery so that the viewer can easily stroll through the works.

"Ten Breaths" 2007, Eric Fischl. Photos : Isabelle Bonzom/Adagp

Emotional locks

The installation is housed in two rooms of the gallery. Three sculpture groupings are gathered in the big room (“Damage”, “Samaritan” and “Congress of Wits”), while “Tumbling Woman” is presented in the smaller room. Everywhere, Fischl has organized vast empty spaces. Those are visual breathing spaces, emotional locks. Thanks to those quiet moments and breathing spaces, the strong tension of the works takes all its importance. For these molded bodies evoke an awful drama of which upheaval is, however, masterly orchestrated. A progression in the action unfolds from a group of sculptures to another, from left to right in the large room.

First, the spectator views the “Damage” group from above. The scene seems to take place following a carnage and presents people busy around a female body horribly mutilated. The silhouettes are fixed onto flat bases superimposed and lopsided. Then, the “Samaritan” duet shows a man with a virile and elegant figure. Gently, he lifts the body of a limp man. The scene takes place on precariously balanced plates. Violence, suffering and death have struck dreadfully. These solemn scenes of rescue are full of tension, humanity and empathy, yet without expressionist excess. The bodies are dignified and tonic. Dramatic concentration is so strong that it imposes meditation. Finally, “Congress of Wits” is an ensemble of dancers all caught in motion. On wobbly pedestals “Congress of Wits” is formed by a group of female dancers. Half naked and in real scale, each wears a long skirt of transparent crimson red mesh. Their bodies, sometimes androgynous, create confusion. Men? Women? Monsters? Consumed beings but alive.

Separated from his partners, as a free agent, a male dancer completes “Congress of Wits.” His body stands up, arched on his left leg. All those figures are muscular and willowy. One thinks of Degas, but above all, one thinks of El Greco. Totally naked, the male dancer seems an écorché, as the texture and the colors of the material evoke muscles, heat, sweat, combustion and open flesh.

Undulation of a monumental wash drawing

Lit by spotlights often put on the floor, the sculptures are multiplied by the shadows they cast on all the surfaces of the room: walls, ceiling, and floor. Shadows link the elements together and create relations and rapprochements between the groups. The silhouettes of the visitors and their shadows are mixed with those of the sculptures. Strolling about, the viewer feels the sensation of a wave motion.

Shadows are more concentrated around “Damage.” They are very dense for “Samaritan”, while the shadows of “Congress of Wits” are lighter and more numerous. The bodies dilate and dilute within the space. As in a monumental wash drawing, those shadows are like supple ink drawings more or less thinned up on the surfaces. A shadow distorts a pose, accentuates a movement; it stresses a gesture and punctuates an outline. A shadow disinforms and dissolves bodies; it also reveals passages and instants. It re-interprets. Thus, the free agent of “Congress of Wits” will eventually dance with his partners to the point of touching them with his own shadow. He will drag the Samaritan with him as he runs. Thus, Fischl leads into an amazing dance of death, fluid and rhythmical.

Slightly isolated “Tumbling Woman” is placed in the center of the second room. From the first room, one already sees her, curled up, as if she were falling to the ground. Without a base, she stands energetically on her shoulders and neck, her body twisted, her legs rocked to the left, in an impressive equilibrium. She struggles with energy. As if she were on a stage or on a construction site at night, the zenithal and point-source lighting falls on her and creates strictly designed shadows that are pressed onto the floor. Two shadows overlap and draw a distinct silhouette which figures a body in movement. Shadows give us the impression that the woman is picking herself up, walking and slipping away on tiptoe.

Experimenting the power of the shadow

The statements and writings of art historians and philosophers such as Michael Baxandall, Victor I. Stoichita and Baldine Saint Girons* remind the reader of the visual strength of the shadow and penumbra. They, literally, shed light on the aesthetic stakes. Shadow traverses cultures and centuries, from the Myth of the Cavern and the Origins of Painting to Bacon, Boltanski or Kentridge, via Rembrandt, Goya, Spilliaert and Calder. “Light eats away at everything,” said James Ensor. Shadows swallow and plunge the viewer into the unknown.

Shadow, in Eric Fischl’s art, plays an important role. In his painting, it cuts sharply and floods the scenes. It goes through the screen of the canvas and introduces rhythm onto the surface. Shadow scratches and scarifies the surface. The shadow is hard and black. In “Ten Breaths,” the shadow lives in the space and amplifies the scene. Shadow surrounds us and embraces us. It dances. Because of the special use of the shadow, this ensemble of sculptures becomes a real installation. In the gallery space which is made to appear as if almost underground, the visitor experiences something that upsets and allows him or her to discern possibilities and transcend horror.

Isabelle Bonzom, June 2009

* Michael Baxandall "Shadows and Enlightenment" (2005), Victor I. Stoichita "A short history of the shadow" (1997), Baldine Saint Girons "Les Marges de la nuit. Pour une autre histoire de la peinture" (2006)

Cathy Stearns and Marie-Christine Bonzom contributed to the translation of this text in English.

First published by CultureCie.

Read additional comments by Isabelle Bonzom about the Tumbling Woman in her lecture Delicious Gravity and watch her additional take about the woman in Eric Fischl's work in her lecture Off with their heads!