ISABELLE BONZOM

CLAUDE F. BAUDEZ, A MAYANIST

Claude-François Baudez is a French archaeologist and iconologist, specialized in the Mayas and Precolombian cultures. He is the author of numerous books, among them "Lost cities of the Maya". He has written several essays, notably "Pretium Dolores, or the value of pain in Mesoamerica", in "Blood and Beauty. Organized violence in the art and archaeology of Mesoamerica and Central America". He was the co-author of "Capture and Sacrifice at Palenque".

Read what anthoroplogist Louise Iseult Paradis wrote about Claude Baudez' book "Une histoire de la religion des Mayas : du pathéisme au panthéon", here in this review.

Read the obituary published by the Boletin del Museo Nacional de Costa Rica which talks more precisely about Claude Baudez' work in Costa Rica.

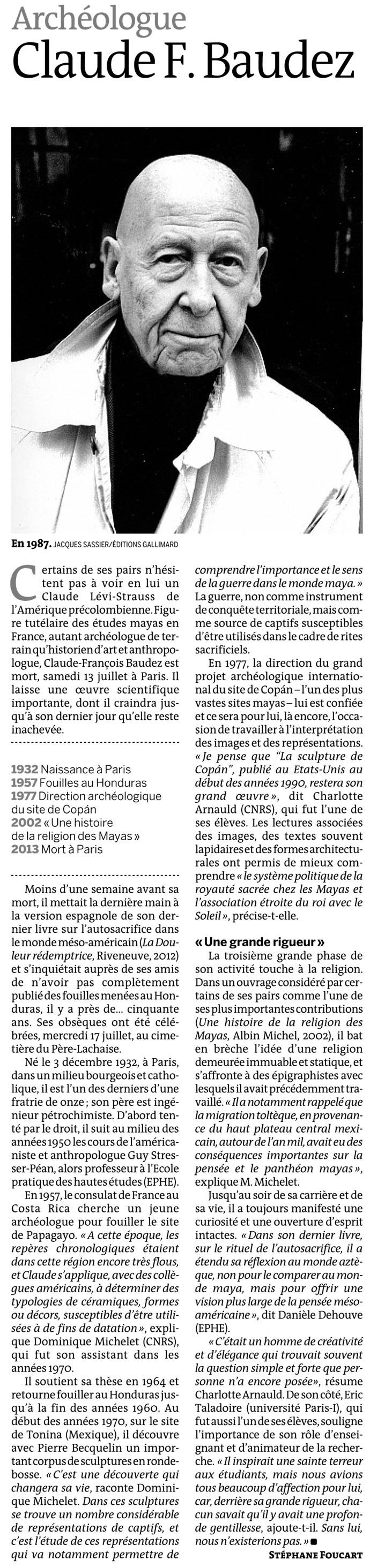

Tribute to Claude-François Baudez, who passed away on July 13, 2013, published in the July 20 weekend edition of Le Monde newspaper :

Archaeologist, Claude F. Baudez

In the eyes of many of his peers, Claude François Baudez was the Levi-Strauss of pre-Columbian America. The archaeologist, art historian, anthropologist and tutelary figure in Maya studies in France died Saturday, July 13 in Paris. He leaves an important scientific body of work, which until his last day he feared would remain unfinished.

Less than a week before his death, he was finalizing a Spanish version of his latest book on auto-sacrifice in the Mesoamerican world (La douleur rédemptrice, Riveneuve, 2012) and spoke with his friends of his concerns about not having completely published his finds from excavations in Honduras nearly fifty years ago. His funeral was held on Wednesday, July 17, at the Pere-Lachaise cemetery.

Born December 3, 1932 in Paris to a middle class Catholic family, he was one of eleven children. His father was a petrochemical engineer. After initial attempts at studying law, in the mid-1950s Baudez followed the courses by Americanist anthropologist Guy Stresser-Péan, then a professor at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Études (EPHE).

In 1957, the French consulate in Costa Rica was looking for a young archaeologist to excavate the site of Papagayo. "At that time, the chronological markers in this region were still very vague, and Claude and his American colleagues attempted to establish typologies of ceramics, forms and decoration for dating purposes ” according to Dominique Michelet (CNRS), who was his assistant in the 1970s.

He defended his thesis in 1964 and returned to fieldwork in Honduras until the late 1960s. In the early 1970s, working at the site of Toniná (Mexico), he and Pierre Becquelin uncovered a significant group of sculptures in the round. "This discovery would change his life,” said Dominique Michelet. The sculptures included a considerable number of representations of captives; it was the study of these representations that helped him understand the importance and meaning of war in the Maya World. "War, not as an instrument of territorial conquest, but rather as a source of captives for use in sacrificial rites.”

In 1977, he was named director of a major international archaeological project at Copan, Honduras, one of the largest Mayan sites known. This work afforded him the opportunity to study the iconography and interpret images and representations. "I think Maya Sculpture of Copan, published in the United States in the early 1990s remains his greatest work," said Charlotte Arnauld (CNRS), one of his students. His readings of associated images, often terse texts, and architectural forms have allowed for a better understanding of "the political system of Maya sacred kingship and its close association with the sun” she explains.

The third major phase of his research focused on religion. In a work considered by some of his peers to be one of his most important contributions -- Une histoire de la religion des Mayas (A History of the ancient Mayan religion), Albin Michel, 2002 --, he argues against the idea of an immutable and static religion, differing with epigraphers with whom he had previously worked. "He reminded them that the Toltec migration from the central highlands of Mexico, around the year one thousand, had important consequences for Maya thinking and their pantheon" Michelet says.

He always showed such great curiosity and an openness of spirit even to the very end of his life. "In his last book on the ritual of auto-sacrifice, he extended his reflections to the Aztec world, not to compare them to the Maya, but to provide a broader vision of Mesoamerican thought" Daniele Dehouve said (EPHE). "Claude was a man of enormous creativity and elegance, who often asked the simple and powerful question that nobody had asked before" says Charlotte Arnauld. Eric Taladoire (University of Paris-I), another of Baudez’s students, emphasizes the importance of his teacher in his own research role. "He inspired a holy terror in his students, but we all had great affection for him, because behind his tremendous rigor, everyone knew that there was a deep kindness,” adding, “without him, we wouldn’t exist.”

Stéphane Foucart, in Le Monde, July 19, 2013

Kindly translated by anthropologist Jane Walsh